Remember outlining essays back in school? Before you even started writing the essay, teachers would make you write your thesis statement, 3 or 4 topic sentences, and then a few bulleted detail sentences beneath each topic. It felt like just an extra homework assignment, designed to stretch out the writing exercise, but it was an actually effective way to teach students how to structure their essay and stay on topic. So, when we grow up and develop into writers, why have we abandoned the practice?

Well, for one, the more we practice writing, the more we internalize the outline process. We learn how to seek out the skeleton of a story or poem or essay in our heads as we brainstorm. So, there’s no real need to write it all out. Another reason is that there is a bit of a stigma when it comes to outlining. Outlining is a beginner’s tool. It’s something that people who don’t know how to write or control themselves need. It’s a handicap, the sign of a novice. Outlining is training wheels.

Guess what? I outline all the time. I found that when I picked up the practice again, my writing became much more enjoyable. It cut down on backtracking, gave me a sense of direction, and allowed me to focus on discovering all the fun stuff along the way of creating a story. Now, I don’t outline in the way we were taught in school. I’ve refined the process into three different methods, tailored for my particular style. Here’s the first one, and I’ll cover the other two in additional posts:

The Breadcrumb Method

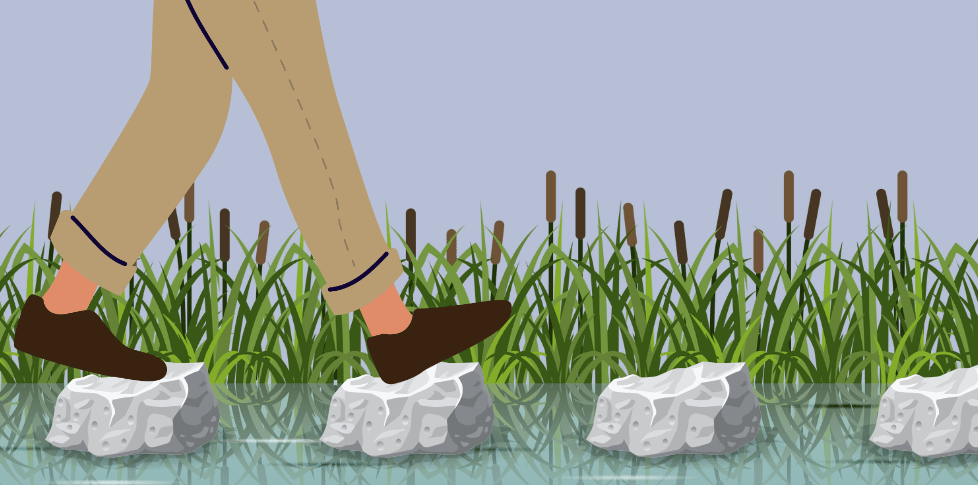

I use what I call the “Breadcrumb Method” when I have a particularly dense story or a story that is very plot driven. This refers to the Hansel and Gretel fairytale where the children ventured into a forest and left a trail of breadcrumbs on the ground so they could find their way home.

I’m big on making sure my characters act in normal, believable ways. Every action leads to a reaction, and every piece of dialogue creates another line of dialogue. So, if an action is illogical or a line of dialogue doesn’t sound believable, every subsequent event will be based off those mistakes. This creates a domino effect of doom. Outlining helps me with this. I don’t do the traditional thesis > topic sentences > detail sentences, but I have found that a simple bulleted list of the events and plot points helps me work out the integrity of the story. Here’s an example:

- Dorothy lives in Kansas on a farm. [Describe farm life]

- One day, her dog bites a rich lady who orders the police to euthanize it. Dorothy wants to protect her dog, so she runs away with it.

- Dorothy meets a fortune teller who tells her to return home because her aunt is heartbroken. But when she does, there’s a tornado, which picks up the house with her in it and drops her off in a new world.

- Dorothy steps out and looks around. [Describe the new world]. She meets a good witch named Glinda and a host of little people called Munchkins. They explain that she has arrived in Munchkinland in the land of Oz.

- She discovers that the house has been dropped on someone wearing ruby slippers. An evil witch, known as the Wicked Witch of the West, appears to retrieve the slippers, but the Glinda transports them onto Dorothy’s feet. She tells her to keep them on, as they are very powerful. The Wicked Witch has no power in Munchkinland, so she disappears after threatening Dorothy and her dog.

These bullets are enough to keep the direction of the story in sight for me. There is no need to write out every detail, as indicated by the bracketed notes. This outline creates a great reference point for me if I start to feel myself wandering away, and it also allows me to see the plot pared down. From here, I can examine it and adjust before I commit to adding the details.

The next method I’ll talk about is the Trail Marker Method.

Leave a comment