This is a lesson that took me a long time to learn. Let’s get the definition out of the way. Word economy is the practice of using fewer words to say more. With practice, you can internalize the practice into your way of thinking so that you can comfortably write economically without much effort. However, when you are first starting out, it means that you will be doing a LOT of revising.

When we talk about economical writing, we’re looking at redundant words, clichéd language, and weak word choices. The purpose of word economy is to make your writing as clear, succinct, and strong as possible.

I remember when I was in college, I took a poetry writing class. The professor, who would eventually become my mentor, kept hammering me about being too wordy.

“Be more economical,” he’d say every time.

(He was actually much nicer about it.)

One day, I was fed up, and I turned in a poem that was five short lines. He said, “Now you have it!”

It’s a difficult technique to master because it’s something that you need to be aware of ALL THE TIME. It takes practice, but if you work on it enough, you will begin to strengthen not only your writing, but your way of thinking. Here are some tips to help you get started:

Try to use words that can pull double duty.

Here’s a middle school throwback: remember homonyms? Homonyms are words that are spelled or pronounced the same but have different meanings.

It’s a little difficult and might only apply in special situations, but if you can find words that can apply both meanings in the same context, you can really create a memorable punch. I find that this works especially well with poetry. Here’s an example from that poem I mentioned earlier:

When should I stop noticing

The leaves on the frigid lawn, marooned,

Littering the grass like raspberry stains,

Collecting rainwater with cupped, begging hands,

Drying like your left-behind roses?

First of all, go easy on me, alright? I wrote this in a college poetry class, and I’m definitely not a poet anymore. In this case, marooned serves as both a color that connects with raspberry stains in the next line and a verb meaning and point of the poem, being left behind. By finding words and phrases that hold multiple meanings, you not only save space and words, but you can also create more depth to your work.

Watch out for passive voice

Most sentences have a subject – a person, an animal, a thing, whatever – and that subject does something – the verb of the sentence. When your sentence clearly shows the subject, then what that subject does, that’s active voice. Active voice makes your writing stronger, clearer, and more direct. With passive voice, the subject is acted upon by another subject or object of the verb. Passive voice separates the subject from the action, leaving more room for confusion and misinterpretation. I know that sounds weird, and I probably didn’t explain it well, so here’s an example:

Active voice – Margot chased the cat.

Margot is the subject, chase is the verb, and the object that is receiving the verb is the cat.

Passive voice – The cat was chased by Margot.

This is still technically relaying the same information, but the structure of the sentence is drawing your attention away from the subject and putting it on object.

This isn’t to say that passive voice should be eliminated completely. There are definitely some good uses for it. For instance, if you are writing a scene meant to misdirect the reader or add confusion (like in a whodunit murder mystery), passive voice can really add to the atmosphere. However, if you want to be clear and sharp, it’s best to change your sentences to active voice, if you can.

Pick strong verbs

You can use strong verbs to convey large amounts of information. Check this out:

Michael cried loudly in convulsive gasps.

Michael sobbed.

We can all picture what sobbing looks likes. We all know that sobbing is much more out of control and intense than simply crying. Therefore, by using “sob,” we can eliminate the rest of the information in the first sentence. Use common knowledge to your advantage. Whenever can get your readers to add in their own details, do that! (Unless you need them to envision a very specific thing, of course.)

Make your scenes accomplish multiple things

You don’t need to write one scene for one purpose. You can use a scene to establish the setting, do some character work, and advance the plot.

Sharon lay in her bedroom but found it impossible to sleep. She was used to the country, to the singing of crickets and cicadas, the sound of a midnight breeze whistling softly through her cracked windows. But in her new apartment in the city, the urban noises – the honking horns, the constant shattering of glass, the loud, echoing arguments – felt loud and foreign to her. Every night was the same, and this evening, she’d had enough. She got out of her bed and stomped to the bedroom window. As she pushed it open, she didn’t know what she was about to say; she simply opened her mouth and let the words rush out.

In this scene, we establish a little bit of her prior life and her current setting. We show that she is uncomfortable, and we also advance the plot by having her get out of her bed and take action. Writing separate paragraphs for all of these purposes would be unnecessary.

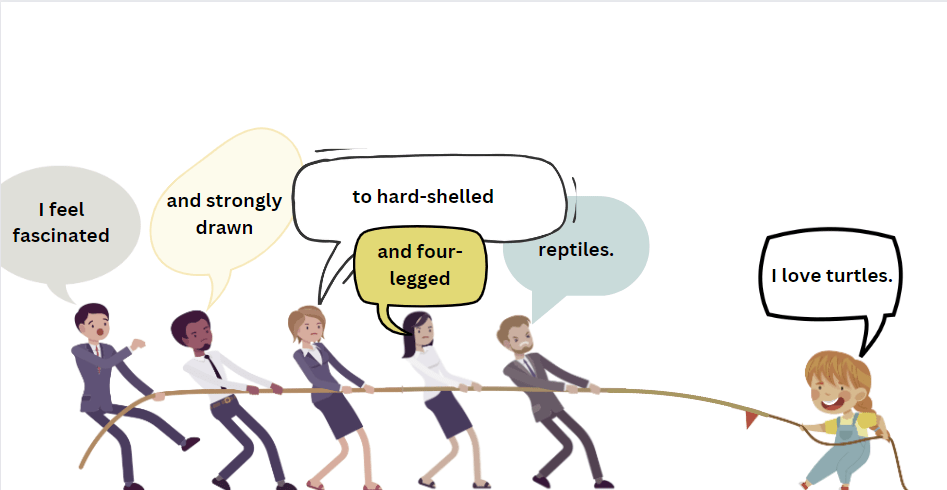

Restrain your dialogue

Unless you are writing a character who is verbose and talks a lot, or if you are writing a fantasy or historical story where people speak abnormally, you should write dialogue as close to normal speech as possible. People don’t always speak in full sentences. We pause, we shorten our own language, we interrupt each other, especially when we are comfortable with each other. People don’t normally say, “Would you like to watch the television with me?” They’ll say something like, “Wanna watch TV?”

Compress your language and avoid empty, useless conversations by using dialogue to advance the plot or set a scene.

Hunt down those adverbs

Adverbs are words that modify an adjective or verb.

She said, quietly.

He pets the dog gently.

She screamed loudly.

Adverbs restrict and narrow the meaning of the verbs, and as a general rule, if you find yourself using adverbs, it usually means your verbs are weak. Let’s look at the examples above:

Each verb in the above examples is very simple and weak. Choose verbs that are stronger and convey more meaning. It can look something like this:

She said, quietly -> She whispered.

He pets the dog gently -> He strokes the dog.

She screamed loudly -> She screeched.

Now, of course, nothing is 100%. One of my favorite things about writing is that you can find situations where breaking the “rules” just works and can even been seen as innovative and exciting. These are all just guidelines. Thanks for reading!

Leave a comment